I like to try and immerse myself in the world of the ancestor I am working on. Context can provide important clues and paths to follow when trying to find appropriate genealogical and historical documents. For instance, it wasn’t until I went to West Yorkshire and travelled around there that I could with confidence trace my Ellison family back to the late 1600s. The context of the landscape and topography of the area were important facets of understanding this family.

As you know, I’ve been working on William Ralston (abt 1750- aft. 1801) of Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania. I know there is a microform I need from the Presbyterian Historical Society and some court records at the Pennsylvania State Archives, but both of these archives are closed due to the pandemic. I am trying to find a microfilm reader near me, as I think the PHS will loan me the film via interlibrary loan. The Library of Michigan is still closed so I cannot use their readers.

What I am certain of is William and his brother Robert Ralston were Scots Irish Presbyterians. I am not certain where they were born, my guess is Northern Ireland. We know with certainty that William claimed his land in Westmoreland County in 1769, according to a court record.

I have found a newspaper reference from The Pennsylvania Gazette that a nineteen-year-old William Ralston arrived in 1769 in Pennsylvania as an indentured servant and then ran away, and that he was Irish. For some reason, I am leaning toward this William as being mine. I think it is the idea of him making his way out to the frontier and claiming land in the wilderness, during hostilities with the indigenous people. Really imagine this in your mind, he showed up in the woods and had to build himself shelter, hunt/grow/find food to eat. There was no real town or settlement here at this time: Hanna’s Town was a few years away still. And he didn’t leave this land until after he lost the land in 1801 due to William Perry not fulfilling his obligations. I can see being a wanted fugitive indentured servant as adequate motivation to endure these hardships.

His brother Robert was on the other side of the Big Sewickley Creek (One side was called Huntingdon and the other Hempfield), but I think he followed William out there. Just because his name is William does not mean his father’s name was William. We do not know the birth order of this family and if he is first born he would have been named after his paternal grandfather. I am not sure his son William is his first born.

Everyone from both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland was termed “Irish” in the 1700s.

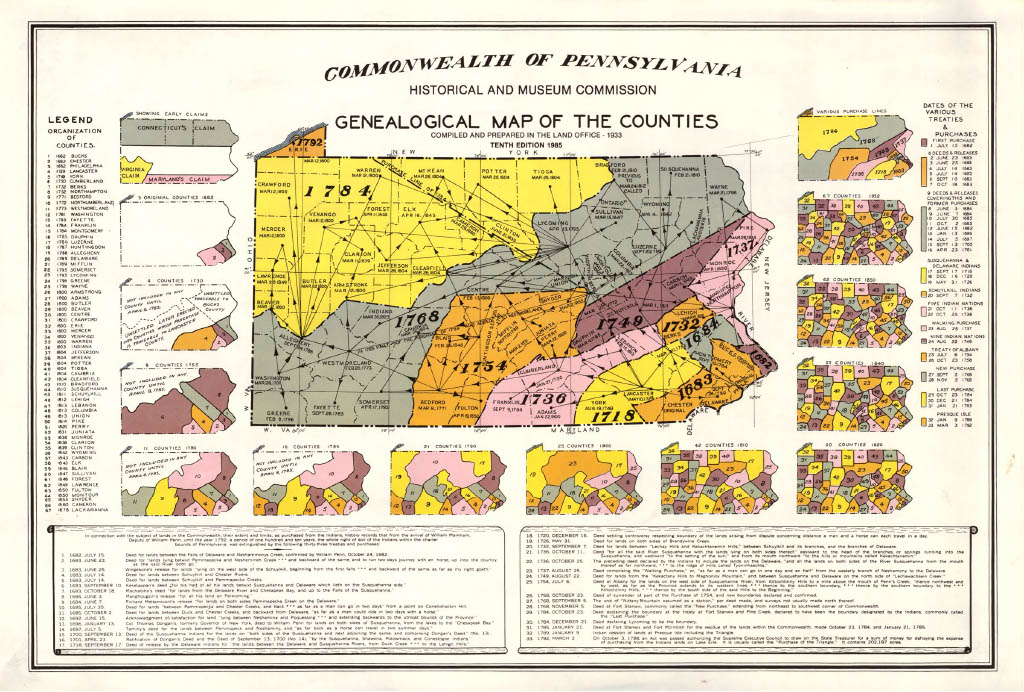

Here is a fabulous map I found to help picture the movements of the settlers and the changes in Pennsylvania. This map helped me ascertain that it is possible William was in Mercer County in 1800. When William and Martha had to sell their land in Westmoreland County, they listed themselves as being in Allegheny County at the time (1801). You can see that Mercer had just been formed out of Allegheny County in 1800.

Therefore, this is probably William and Martha in Mercer County on the 1800 census:

The census lists

Name William Rolston

Home in 1800 Mercer, Pennsylvania

Free White Persons – Males – 16 thru 25 1

Free White Persons – Males – 45 and over 1 WILLIAM

Free White Persons – Females – 10 thru 15 1 ISABELLA

Free White Persons – Females – 16 thru 25 1 JENNET

Free White Persons – Females – 45 and over 1 MARTHA

Number of Household Members 5

William had five sons: John (1776-1849), David (1778-1859), Jeremiah (1786-1847), Robert (1788-1835), and William (??-??). Who is the son living with them in 1800? Robert would have been twelve and Jeremiah fourteen.

Where were William’s minor sons in 1800? There should be at least two sons listed with him, unless one was apprenticing somewhere or with an older brother, such as David or William.

It is important to note that the two daughters were not married at this time. When searching for what happened to them, we can look for marriages after 1800.

Now I can try and locate William’s burial.

John was living next door. Here he is on the 1800 census with his family. The map above explains why in published articles about John he is listed as having traded his land in Lawrence County for land in Butler County. Lawrence County was formed from Mercer County in 1849.

Name John Rolston

Home in 1800 Mercer, Pennsylvania

Free White Persons – Males – Under 10 1 WILLIAM

Free White Persons – Males – 16 thru 25 1 JOHN

Free White Persons – Females – 16 thru 25 1 ELIZABETH

Number of Household Members 3

I have that John’s son William was born in 1800.

I just finished the book “The Scots Irish of Early Pennsylvania” by Judith Ridner (Temple University Press, 2018) and I recommend it.

It’s not a very long book, but it gives an overview of the Scots Irish (as they called themselves) and their migration from Scotland to Northern Ireland in the 1600s and then to America in the 1700s. It gives a good understanding of the politics of their time, their background, and their culture. The Scots Irish Prebyterians were seeking economic opportunity, including affordable land, and to be free of religious discrimination. Pennsylvania in particular was welcoming to people of all faiths. England had imposed Penal Laws, and required Presbyterians to pay tithes to the Church of Ireland (Anglican). Being a dissenter against the Anglican church created hardships for the Presbyterians in the 1700s.

One of the interesting things I learned was the importance of the production of linen to the Scots Irish families economic well-being and how this was a women’s trade. The Scots Irish grew flaxseed in America and the women spun this into linen thread which was woven into cloth, as they had done in Northern Ireland.

I can picture Martha Ralston at her spinning wheel, creating linen thread and teaching Jennet and Isabella to do the same.

Another fascinating tidbit is the Scots Irish carving of tombstones.

![The True Image: Gravestone Art and the Culture of Scotch Irish Settlers in the Pennsylvania and Carolina Backcountry (Richard Hampton Jenrette Series in Architecture and the Decorative Arts) by [Daniel W. Patterson]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/5104KKaiYUL.jpg)

There is a chapter on the hostilities with the indigenous peoples and Ridner relays information about a couple of horrific massacres perpetuated upon innocent Native Americans at the hands of a Scots Irish militia mob. The Scots Irish, generally speaking, hated the Indians and were prone to resolving all conflicts with the Indians through violence. The whites simply did not care that the land they were settling most often had been stolen or deceitfully obtained from the local indigenous tribes. Since William served on the frontier in 1780, we can make an educated guess that he most likely perpetuated acts of violence upon Native Americans. Andrew Jackson, president during the removal of the Cherokee Indians from their lawfully-owned lands which we refer to as the Trail of Tears, was Scots Irish.

William’s grandson, John Jr, married (about 1833) a woman, Nancy Agnes, who was both white and Native American and her son, Millen, married (about 1861) a woman who was white and also Native American.

The notes contain references to other books/articles I want to read now, such as Irish Immigrants in the Land of Canaan: Letters and Memoirs from Colonial and Revolutionary America, 1675-1815 (Oxford University Press, 2003); The True Image: Gravestone Art and the Culture of Scotch Irish Settlers in the Pennsylvania and Carolina Backcountry (University of NC Press, 2012); Redemptioner and Indentured Servants in the Colony and Commonwealth of Pennsylvania by Karl Frederick Geiser, supplement, Yale Review, 10, no. 2 (August 1901); The Scotch-Irish of Colonial Pennsylvania (UNC Press, 1944); Breaking the Backcountry: The Seven Years’ War in Virginia and Pennsylvania, 1754-1765 (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2003).